Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 03:03 am

You make the transition from PhD student to PhD candidate after you complete all your coursework and your comprehensive exams (if required). A PhD candidate’s sole task is to conduct their research and write their dissertation.

In other words, a PhD student is still completing their coursework. They could be on the first day of their PhD program. A PhD candidate has completed all of the requirements for their degree except their dissertation (yes, that’s the infamous “all but dissertation” status).

PhD candidacy means you’re a PhD in training. Now you’re ready to spread your wings a little–with some guidance.

Your time as a PhD candidate is your chance to demonstrate that you are ready to be an independent scholar. It’s also your chance to screw up and have that be okay–to have support. Your committee will help you. Since it’s the first time you’ll go through the process of creating and performing a study on your own, there’s no reason to believe you’ll be perfect at it. That’s why the process is designed so that your committee can give you guidance.

But besides the simple definition above, what are the implications of being a PhD candidate vs student? Turns out, there are many important differences. Without keeping these in mind when you become a PhD candidate, it’s easy to spin out and get off track and not understand why.

PhD Candidate vs Student: What Are the Differences?

While “PhD Student” and “PhD Candidate” are both steps on the journey to getting a PhD, there are significant differences between them. Here are some of the differences between PhD candidate vs student.

Lack of Structure

When you’re doing coursework, there is structure; there are assignments and deadlines. Of course, in graduate coursework teachers aren’t on top of you to turn in assignments like they would be in an undergraduate program. However, there is a deliverable (final project, test, etc) that you have to complete each quarter. You have things to complete by a certain time in order to move forward.

Once you become a candidate, there’s no syllabus and there are no due dates. It’s completely up to you to move forward in the process.

Some people find it hard to make the transition to the lack of structure that comes with being a PhD candidate.

Academic Writing

Academic writing skills become really important when writing your dissertation–more important even than they were during the coursework phase of graduate school. Academic writing is essentially a new language, with very specific meanings and requirements.

For example, you can’t just say “people believe x or y,” you have to say who they are and how you know that, giving citations to back it up. Many words (like “significant”) have very specific meanings and can’t be used the way you might use them in speech.

As a PhD student, your professors should be teaching this language to you, so that as a PhD candidate, it will come as second nature.

How Many People Do You Have to Keep Happy?

Here’s another difference between being a PhD student vs PhD candidate: as a PhD candidate, you reduce the number of people that you have to keep happy.

As a student, you have to keep in mind the requirements from each professor teaching your classes, as well as matriculation requirements from the department, preferences and advice given by your advisor, and even the research interests of the people for whom you’re writing papers.

Once you become a candidate, it’s just your committee that you have to keep happy, meaning that those are the people who will hold you accountable and outline the requirements for completion of the degree. For that reason, you’ll want to choose your committee members with care.

Hopefully, by the time you need to choose your committee, you’ll have encountered professors who are intrigued by your research interests and with whom you feel personally and professionally compatible.

Freedom to Choose

When you become a PhD candidate, you get to work on what you want to work on. You can pursue the topic that interests you instead of whatever goes with the course you’re in. It’s a time to really apply all those skills you were accumulating in the classes. For example, the statistical procedures you learned in stats classes and theories you learned in the courses for your discipline.

This is the stage of culmination, when everything you’ve learned becomes not the goal, but the foundation for your own body of work. It’s one of the exhilarating (and sometimes intimidating) parts of being a PhD candidate vs a student.

Expectations and Support

Faculty often use the “go wander in the woods” approach for PhD candidates. It’s essentially like hearing, “Go find things and come back to me when you’ve got something.” They’ll usually tell you when it’s not enough, but they might not give you much direction about what they’re looking for beyond that.

The reason for this is to encourage independent scholarship. They want you to have the opportunity to build your own case for why and how this topic should be studied. But this first foray into academic independence can be quite a challenge.

When they tell you to “go wander in the woods,” they’re not even telling you what kind of tree to look for. Sometimes you get specific directions, but sometimes you get vague answers like “go look for more.” This can be frustrating. Many clients come to me because they need more direction, which is understandable.

In your coursework, you were often given studies to read or asked to find studies on particular topics that relate to the course topic. Dissertation research is more nebulous. Your committee members want you to decide which directions to go in and which kinds of studies best relate to your research questions.

They won’t be asking you for the “right answer.” They’ll be asking you, “Why? Justify what you did or plan to do.”

PhD(c)

Here’s another difference between PhD candidate vs student: a PhD candidate can put “PhD(c)” after their name, indicating that they have achieved status as a PhD candidate. However, I suggest using caution with this designation. The APA has expressed concern that its use may be misleading to the general public and cause people to believe you have a PhD.

PhD Candidate vs Student: An Interview With a PhD(c)

Did you notice a change in how professors viewed you, once you moved from “student” to “candidate”?

Yes. It actually happened during my comprehensive exams. Before that, when I had been asked a question, the professor already knew the answer and was asking to see if I knew also. In my comprehensive exams, I had become the expert and my committee members were actually asking questions out of interest.

We were all pieces of a puzzle at that point. Instead of them saying, “tell me about John Dewy’s influence on education in the 1920s,” they asked, “How do you think Dewey influenced the school system’s openness to parental involvement in schools?” The professor who asked that was genuinely interested, because she was an expert in educational history but had not specifically studied parent involvement in schools, as I had.

That moment represented a big shift for me; it meant that as a PhD candidate, I had to then take responsibility for my own learning, because nobody knew as much as I knew about that particular thing.

It’s exhilarating on one hand, because you suddenly realize you’re the expert. On the other hand, it’s scary because we’re used to somebody else knowing the answer, being able to correct us if we’re wrong.

A Narrowing of Scope

It sounds like your topic was centered on something very particular, so maybe not a lot of other people have studied what you want to study?

Yes, that’s true. When you go through a PhD program your research area is pretty narrow. You start out with a general interest in something, but as you go through your classes, specific areas start to stand out.

I started out with an interest in egalitarianism in public education, but my own past experience combined with some seminal texts to direct me toward parent involvement in schools, specifically. Some books and articles showed me that how schools treat parents can be an indicator of egalitarianism, maybe a clearer one than any rhetoric about the students.

So, there’s this winnowing effect, as you move forward. Your professors love to watch this, too. Especially in the smaller, seminar classes, they seem to be waiting to see what makes your heart beat faster.

Passion

Speaking of your heart beating faster, is one distinction of the candidacy phase to have more passion about the work you’re doing?

I think that’s ideal, for sure. It doesn’t always happen, because some professors are really after students who will jump onto their research platform, because they can piggyback on the students’ research to get more publications. Good committee chairs, though, will want you to find your own path toward something you can happily spend a lifetime studying.

I suspect that one of the reasons people don’t finish their dissertations is because they weren’t really passionate about the topic in the first place. It’s only one possible reason, but it should give a doctoral student pause.

It’s really hard to finish a PhD, so you want to knock down any barriers to finishing. Being passionate about the topic will keep you going when things feel onerous. It’s like marrying someone with a sense of humor — even when you’re not getting along very well, there’s something you can always appreciate about your spouse.

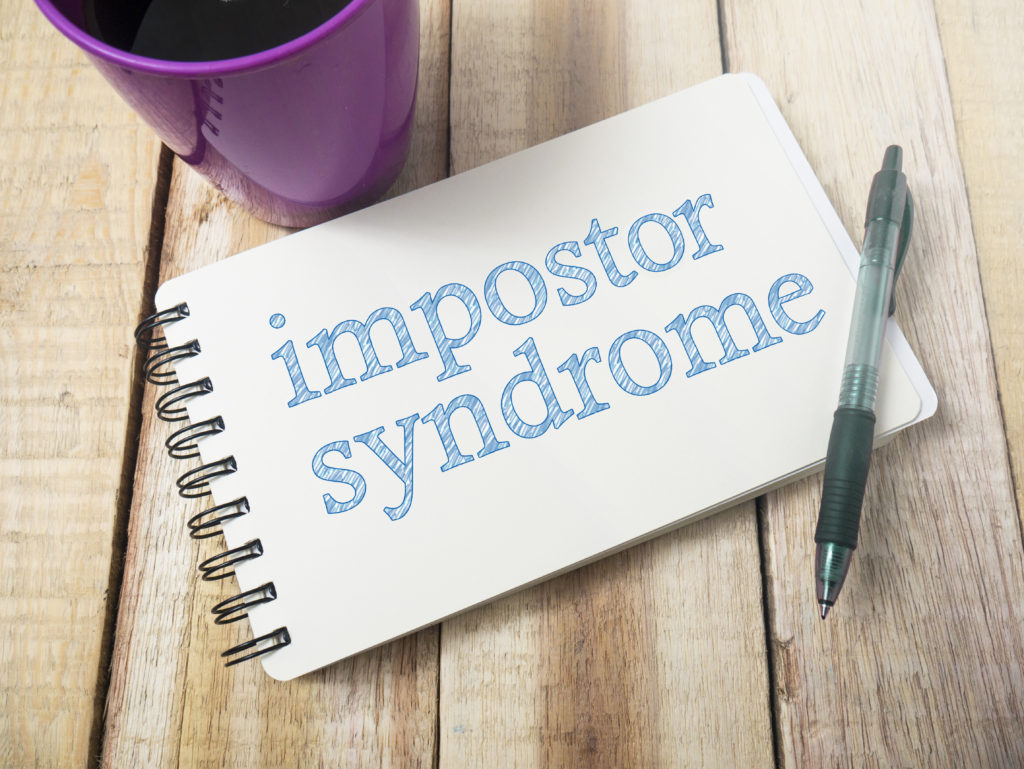

Imposter Syndrome

What about “imposter syndrome”? Does that come into play when you become a candidate?

It sure did for me! To be one of the only people who’s an expert in that field feels like a huge responsibility because people are depending on you. Your research has to be accurate because people will be making policies based on your conclusions.

Even with good intentions, your conclusions can be erroneous, and there are plenty of historical examples of policies being made on the basis of erroneous conclusions. The consequences can be enormous. And that’s all on you!

So then the questions become, “Am I really up to this?” “Who am I to drive policy?” “I’m just a fallible human being, so why would (or should) anyone listen to me?” Especially right after comps, I was thinking, “How could I be the expert? Nothing really has changed about me; I’m still the same person. Yesterday, I was a student, but today I’m an expert?”

My observation is that this happens with women more than men, probably because women in authority positions are more often questioned than are men. But even for men, this seemingly sudden transformation can make you worry that you’re not qualified for the responsibility you’re being given.

The thing is, It’s not really as sudden as it seems. You’ve been studying something for, say, four years, so you have a claim to expertise. And you’ve been narrowing your interests all along the way, so you’ve been slowly building up your expertise.

Besides, in many good schools, you get warned a lot about how easy it is to make a mistake in research and how easy it is to make false conclusions. They beat that into you so much that it can become a constant doubt.

In most primary and secondary schools, and sometimes even in college, they teach you to sit down, shut up, and learn something. For people to suddenly be saying, “tell me what you think,” can be challenging. I suspect that that’s another major reason people who finish their coursework don’t complete their dissertation: they’re not sufficiently prepared for this shift in roles.

Suggestions for PhD Candidates

Having been through this shift yourself, do you have any advice for students in this stage of their process?

Mostly, I think it’s a matter of taking personal responsibility and seeing yourself in a new light. It helps me to consider this process as a transformation — like a caterpillar into a butterfly. The “student” stage is the caterpillar stage, where you’re eating the milkweed, the knowledge, to nourish you.

Then there comes a time when you’ve got to stop being a consumer and transform into a real researcher. That’s like the metamorphosis stage when the caterpillar is in the chrysalis, melting down. (And I have had plenty of meltdowns myself in this stage!) That’s when you’re on your own, writing the dissertation.

That chrysalis stage is a real slog. You try as hard as you can, and your proposal still gets rejected — twice. Or the IRB wants you to structure the study differently, after your committee has already approved it. Or you can’t get enough participants for your quantitative study or enough data for your qualitative study — whatever. It’s the biggest challenge of most people’s life!

But if you stick with it, you actually do get this huge reward. As a butterfly, or a PhD, you bring something unique to the world. You have an important role in society that can potentially change the course of history — even if you don’t envision that in the beginning.

And that’s why the committee makes the process arduous. They want to be sure you’re great at what you do, because there is potentially an awful lot riding on your shoulders. I’m actually grateful for the rigor they demand. I want to feel ready for the role I’m taking.

Ultimately, candidacy is time in the chrysalis. It’s a time of transformation, built on one’s time as a student. It’s a time in the dark and alone, which makes it challenging, for sure. But I trust I’ll eventually emerge strong enough to spread my wings.

Waiting to Get Your Dissertation Accepted?

Waiting to Get Your Dissertation Accepted?